For the second time in less than eight years, I’ve had a newspaper closed out from under me. Although the demise of the Tri-City News is confined to its weekly print edition; we’re still going to be publishing online.

That means I’m still employed; nevertheless, the loss of a physical paper hits hard.

I landed at the News when I came west in 1991.

Back then it was crazy, busy market that was growing exponentially. We went from publishing two editions a week to three to three plus a special insert. Papers were bursting with pages and thick with flyers. The Classified ads usually ran eight to 10 pages.

To help fill all the spaces between ads, we were six photographers deployed seven days a week to cover events from the Vancouver-Burnaby boundary to the far rural reaches of Maple Ridge, from eight in the morning until eight or nine in the evening. We had a studio, film lab and two darkrooms — one for printing colour and another for B&W.

Some of the photos I shot in my first few months at the Tri-City News back in 1991 and now digitally preserved by the Coquitlam Archives. Without them, people living in the area today might not know the Golden Spike Days festival in Port Moody included go-kart races, or that sea lions swam up the Fraser River to chase oolichans and bask on the log booms. Moments like these are rarely covered by papers anymore because resources are too diminished.

Scrolling through the 30 or so web pages the Archive posted of those images on its website was a salve to the news from the day before. It was also a reminder of what we’ve lost as an industry, partly because of the communication revolution that was the advent of the World Wide Web, but mostly because of the newspaper industry’s inability to figure out how to exist alongside it.

With storm clouds for newspapers’ profit margins gathering, photographers were amongst the first to be cast aside. Mobile phones with integrated cameras were everywhere and images contributed by readers out and about, or reporters already at a story anyway, suddenly became “good enough;” who needs prima donna photographers driving around in their cars all day getting up to who knows what between millisecond shutter clicks.

But management’s assessment ignored our ambassadorial role. Because we were out there all day, every day, we became the face of the newspaper for much of the community.

When someone called in to request coverage of a community happening, they usually asked specifically for a photographer to be sent. And when we were at such events, people would inevitably come up to ask if we could put their photo in the paper, not have them mentioned in a reporter’s story

Photographers’ presence in the community every day also gave us a unique insight into its rhythms and evolution, as even the slightest change or deviation would catch our eye and become a possible subject for photographic exploration.

We called those kind of photos — often shot between assignments and without enough time — tour shots or wild art.

On a busy day, they often helped grease the creativity wheel.

When it was slow and the editor needed something to fill a quarter page hole somewhere near the back of the paper even though there was nothing going on, they were a lodestone around your neck, dragging your spirits and emptying your gas tank.

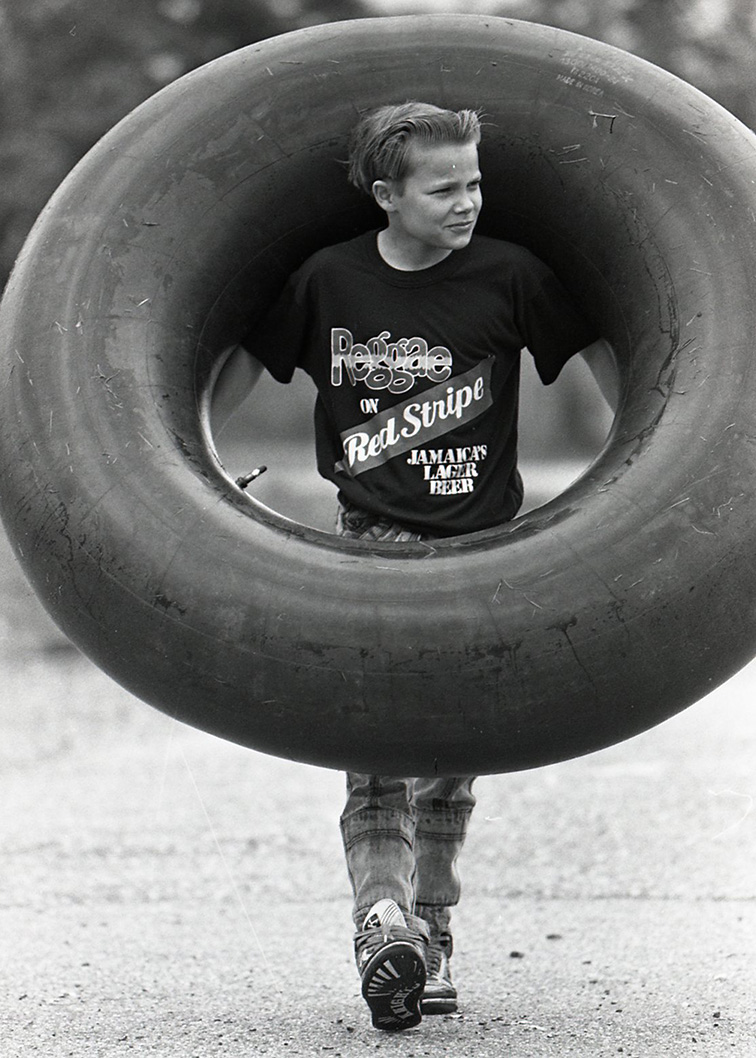

But looking back more than 30 years ago, it’s those images that catch my eye: working the graphic lines of a construction project; the body language of striking refinery workers; the joy of a kid walking down the street with a giant inner tube.

We pass such mundane, routine moments every day, but as photojournalists, we have license to pull our cars over, grab our gear from the trunk and figure out how to turn it into a moment, then go find out more about it so we could write the caption.

Oh yeah, and there was that editor with a hole on Page 36 to fill too.

When they were published, such moments might bring a smile or glint of recognition to the reader as suddenly something they’d passed by themselves took on a new look or context. Thirty years later, though, they’re a glimpse into what the city was like three decades earlier — the clothes people were wearing, the things they got up to, the cars they were driving, the environs in the background, when something now familiar was just new, what has been lost.

They’re an important contribution to the community’s collective memory.

As photo staffs were pared and ultimately eliminated, those moments disappeared from our coverage. The ability to send a photographer to tell the story of an event diminished. With nobody on the street because reporters were too busy in the office churning out stories, newspapers’ connection to the communities they cover started to suffer.

Getting rid of photographers didn’t kill newspapers, but it sure didn’t help either. Without our keen eye to capture the essence of a story in a single frame, see the moment, bring a unique perspective to the ordinary, papers abdicated a bit of their professionalism.

Soon enough our word colleagues in the newsroom would feel the same sting. As their numbers were reduced, the breadth and depth of stories we were able to cover was diminished. Fewer people to do more work meant more errors and missed story opportunities. Once the slide started, it was hard to stop.

Good stuff Mario. I of course can relate to all aspects of it.

LikeLike

Before my time there, but still made me smile (partly because of the historical posterity that it’s now achieved!)

https://searcharchives.coquitlam.ca/index.php/wearing-the-dunce-cap 🙂

LikeLike