This story first appeared in the Tri-City News on June 19, 2018

Alex Stieda owes everything he achieved in bike racing to Coquitlam. Or rather, the city’s hills.

So it’s only appropriate on Thursday he’ll be inducted into the Coquitlam Sports Hall of Fame at the Poirier Sport and Leisure Centre, located about midway between two of the climbs he regularly ascended on his 10-speed he’d acquired from a high school buddy to improve his fitness in advance of the Juvenile hockey season.

It was an unlikely beginning to a career that would make him the first North American cyclist to wear the Yellow Jersey as the leader of the Tour de France as well as compete for Canada at international events like the 1982 Commonwealth Games, 1983 Summer Universiade and the 1984 Summer Olympics.

Stieda’s grinds up Blue Mountain Street and Mariner Way caught the attention of a neighbour two doors down from his parents’ home on Gatensbury, near Como Lake. Harold Bridge was a dedicated randonneur, an eclectic breed of cyclists that enjoy rides of 200 km or more in a day; his wife, Joan, happened to be the president of Cycling BC at the time.

Bridge took Stieda under his wing, showed him how to ride in a group and draft behind other riders to save energy. And when the long, languid rambles of the randonneurs didn’t seem challenging enough for his young protégé, he passed Stieda on to Larry Ruble, who led a group of faster cyclists out of his Maple Ridge bike shop for rides to Mission or Fort Langley, and back.

More often than not, it was Stieda who took the lead and did the most work of their small peloton of 10 or 12 more experienced cyclists.

So Ruble suggested Stieda head to the roads around the University of British Columbia, where veteran racers competed to be the fastest in time trial races against the clock every Thursday evening.

Of course, Stieda cycled there, making the long ride out along 41st Avenue to UBC after school, post his time on the five-mile time trial course, then ride all the way home, pounding his way back up Blue Mountain in the fading twilight.

“When you’re at the end of your rope after riding 100 km, you just do everything to get home,” Stieda recalled from Edmonton, where he’s an account executive for an IT company. “Living in Coquitlam made me stronger.”

Strong enough that he started winning races at the old China Creek velodrome in Vancouver, then eventually a victory in the Canadian track cycling championships that earned him a trip to the junior worlds in Buenos Aries, Argentina.

‘I wanted to do more’

“This is super cool,” Stieda said. “I was smitten. I wanted to do more.”

Stieda started honing his road racing skills with local teams like Gunners and Carleton. Eventually he hooked up with a crew sponsored by a local Rotorooter franchise; they’d train and race through the summer, then unclog drains in the winter.

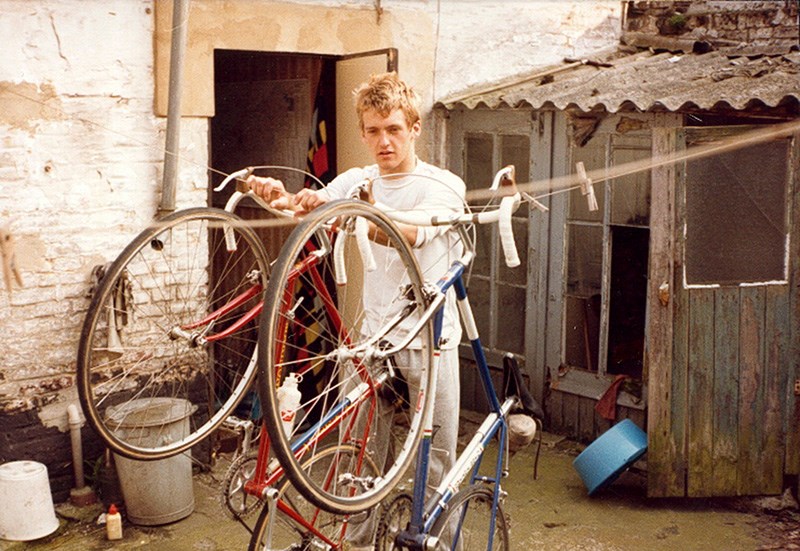

In 1981, Stieda realized to take his cycling to the next level, he’d have to travel to the sport’s spiritual home in Belgium where hardened European neopros banged handlebars, cut deals and maybe got noticed by bigtime pro teams, in kermesse races that could be found almost every afternoon or evening in small towns or villages across the country.

Stieda’s dad secured a $500 grant that paid for a flight to Ottawa, where he dragged along a home-built Fibreglas case holding his steel Marinoni racing bike to a military base in Trenton, Ont., to catch a Royal Canadian Forces flight to Lahr, West Germany and then on to Frankfurt, Germany and Ghent, Belgium, by train.

Stieda, 20 at the time, had no idea what he was getting himself into.

“The guys at the base probably got a kick out of me,” he said.

Midnight arrival

Deposited at Ghent’s train station at midnight, Stieda bounced his bike box over the dark, cobbled streets to find Staf Boone, a sort of Godfather of the local cycling scene who managed a number of apartments in the area that he let out to visiting foreign cyclists pursuing their dreams.

Stieda roomed with an Australian cyclist. Their “cold-water flat” had no hot water, a propane hotplate for a stove, and they went to the bathroom in a shack out back.

“It was definitely a hard life,” Stieda said. “But I was just living in the moment.”

Out on the road, Stieda learned some hard lessons as well. Semi-professional bike racing in Northern Europe has its own culture, its own code of rules and ways of breaking them in the name of survival.

“I didn’t have an opportunity to get intimidated,” Stieda said. “If you weren’t tough mentally, it was over.”

Stieda’s trial by cobblestone got noticed by the newly-formed American team, 7-Eleven, that was built around famed Olympic speedskater Eric Heiden who raced bikes as part of his off-season training, and included another Canadian cyclist, Ron Hayman.

The team invited Stieda to enter some races in North America in the fall when he returned from Europe, and in 1982 he was offered a contract.

No illusions

Stieda said he had no illusions of glory. He didn’t have the lean build of a Grand Tour rider who could rack up big kilometres and recover to do it again the next day for the three weeks of a race like the Tour de France or Giro d’Italia, nor did he have the explosive power to win sprints. He was a domestique, a worker who could sacrifice himself for the team’s leader, haul water bottles, be there if a wheel needed to be swapped out.

That was to be Stieda’s role when 7-Eleven, now a big league professional team on a mission to popularize bike racing in the New World, was invited to the 1986 Tour de France, after two of its members stunningly won stages at the Giro d’Italia the year before.

But somehow, the early stages of the 21-day race around France played to Stieda’s strength of being able to ride away from opponents for 80 or 100 km, just like those rides out to Mission and back home up Mariner Way. Add in some time bonuses he earned along the way, and midway through the Tour’s second day, after an 85-km road stage in the morning that would be followed by a team time trial he barely survived in the afternoon, Stieda climbed atop the podium, got kisses on his cheeks from the podium girls and pulled on cycling’s most famous prize.

“It was really more of a strategic play rather than being the strongest rider,” Stieda said. “I had to figure out how to use my energy in the right way.”

Learning lessons

But Stieda couldn’t bask in his glory, as there were more lessons to be learned the next day. That’s when a veteran Dutch cyclist from another team told him on the road it wasn’t enough to wear the Yellow Jersey, he had to honour it by actually finishing the Tour.

“That hit me like a ton of bricks,” Stieda said. “So I just followed him around every day.”

Stieda did finish the race, in 120th position. But what amounted to his lunch hour in Yellow set the table for an era of North American glory in cycling’s biggest race, including overall victory in the ’86 Tour by American Greg Lemond — his first of three Tour wins — and more Yellow Jerseys worn by fellow Canadian Steve Bauer in 1988.

“It was just an amazing time, we were breaking new ground,” Stieda said, adding the old 7-Eleven teammates still gather for a reunion every five years or so.

• Stieda will not be able to attend the induction ceremonies on June 21. But he is sending a replica of his Yellow Jersey that will be mounted in a display in the lobby of the Poirier Sports and Leisure Complex.