This story first appeared in the Tri-City News on Feb. 9, 2023

An earthquake half a world away is bringing an extra sense of urgency to Port Moody’s own preparation to handle a natural disaster.

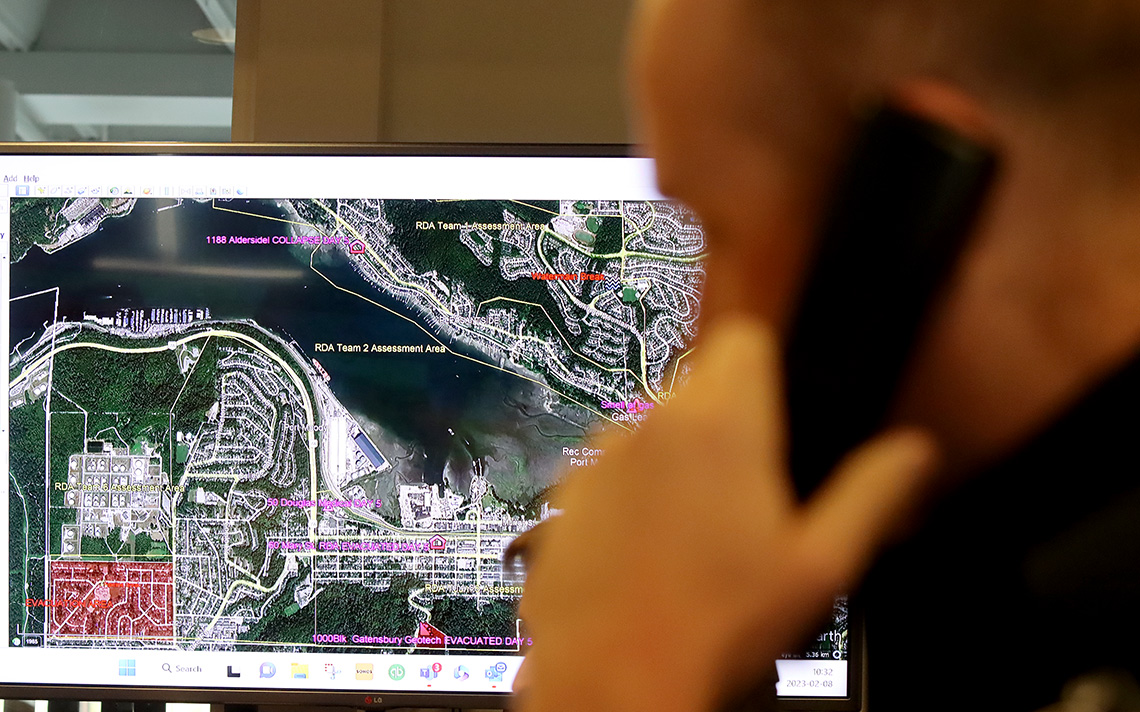

On Wednesday (Feb. 8), more than 50 staff, representing a range of city departments from fire and police to finance and human resources, participated in a province-wide exercise to test its response capabilities to a simulated catastrophe five days earlier.

Port Moody was the largest municipality in the scenario, which also involved agencies from the federal and provincial governments as well as Metro Vancouver.

Kirk Heaven, deputy chief at Port Moody Fire Rescue, said the earthquake Monday (Feb. 6) that devastated parts of Turkey and Syria brought home the reality of a disaster that could strike B.C.’s South Coast at any time.

“It adds impetus,” Heaven said, adding live news coverage from Turkey playing on monitors in the city’s emergency response centre set up in a boardroom on the fourth floor of the Inlet Fire Hall provided a reminder that Wednesday’s simulation was “about learning.”

Heaven said planning for the exercise started last September with the goal of furthering knowledge city staff have gained from previous simulations as well as recent real-world scenarios like the heat dome and atmospheric rivers of 2021 and the annual threat of wildfires.

Wednesday, Port Moody was already in recovery mode five days after a 6.8 magnitude earthquake in the Juan de Fuca Strait. That meant rescue efforts were now shifting to support, making sure displaced residents and their pets have someplace safe to stay, as well as access to food and water, and getting critical infrastructure like water, sewage and electricity, along with transportation, back up and running.

Getting back to normal

“It’s about trying to get back to normal and getting people back to their homes,” Heaven said.

Such an effort presents huge logistical challenges, from just getting around to ensuring there’s enough staff available to cover shifts at facilities like emergency shelters to making sure everyone gets paid.

Coordinating all those myriad details and the communication efforts required to run a recovery effort smoothly takes lots of practice, so when a real disaster hits, wheels are set in motion quickly and automatically.

“It’s imperative we keep it up,” Heaven said. “You have to know your strengths and identify your gaps.

Huge learning curve

Joji Kumagai, Port Moody’s manager of economic development, said the exercise forces him to look at the city “through a different lens.

“You have to understand who is responsible for what so you can act quickly.”

Kumagai said though Wednesday’s exercise was his fourth, the learning curve is huge.

“You really start to understand what a concerted effort it takes,” he said.

In addition to the emergency operations centre packed with people coordinating Port Moody’s recovery effort, a smaller group of about 12 was in another office in the fire hall planning for the next steps of getting the city back on its feet, like bringing in equipment to clear rubble and where to put it.

Over at the Inlet Theatre and galleria, another team was responsible for registering displaced residents and getting them into temporary shelter at the Recreation Complex next door.

Caring for animals and emotions

Even representatives and volunteers from Canadian Animal Disaster Response Team were available to care for pets, although they did forget to pack a bowl for the stuffed Nemo awaiting refuge on a window ledge.

In an alcove, comfortable chairs were set up where traumatized victims could get emotional support.

Heaven said the exercise is funded by a grant from the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM). But bringing together all the disparate players in Port Moody’s disaster response effort is invaluable.

“We don’t want to meet people at the party, we want to see them before the party.”